Dunhill 1929 Shell LC

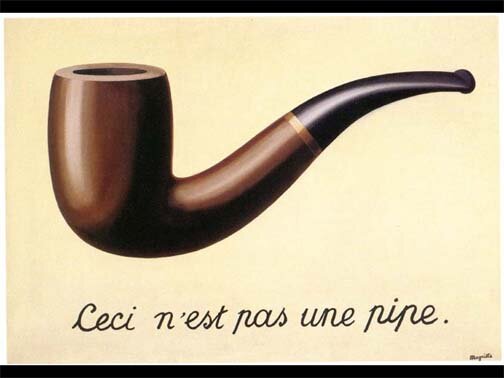

This is a pipe that has received a great deal of attention from a number of quarters, including Alfred Dunhill himself. To understand it fully, we must deconstruct it layer by layer. First, let us consider the pipe qua pipe to see what it tell us. One is immediately struck by its extraordinary size, especially for a pipe from 1929, when tobacco was extremely expensive and most pipes correspondingly small. It is 19 mm long, and 7 mm tall, one of the largest of its type known. It has a tall, rather curiously shaped billiard bowl with a kind of bulge at the front of the heel (about which more anon). A very graceful curved and tapered "swan's neck" shank emerges fluidly from the bottom of the bowl, rising to meet a curved handcut vulcanite taper bit which ascends to a level significantly above the bowl. One is also struck by the depth and detail of the blast, which reveals the internal structure of the briar down to the level of the individual grain, further accentuated by the double staining, with rich red undertones peeking through the dark walnut overstain. We note that the bowl is almost completely surrounded by ring grain, and that the pipe appears virtually unsmoked. This tells us that the pipe was cut from a most remarkable piece of straight grained Algerian briar. Algerian burls are normally quite small, with a relatively thin "cortex" of straight grain. Thus to find a block of this quality would be an extreme rarity. And it received as much as eight hours of careful blasting by Dunhill's best craftsmen to bring it to this point.

When the pipe is turned over to inspect the nomenclature, something odd becomes apparent: the shank was apparently carefully severed and reattached, as there is a distinct line that surrounds its circumference.

One can be certain that this was not a repair, as the grain matches perfectly on either side of the "incision;" and the factory stamped the nomenclature deliberately to span it. There is a very good reason for this configuration, dictated by the fundamental geometry of the pipe, which Lars Ivarsson helped me to understand. This is illustrated in the picture below:

The red line represents the most extreme angle at which a straight passage could have been drilled; but we can immediately see that the airhole would not not even have entered the bottom of the bowl. Moreover, this would have been an extremely dangerous drilling under any circumstances, one that would surely have resulted in a burnout at the top of the shank when the pipe was smoked. The solution which the French pipe makers in St. Cloud had discovered for this problem was to drill a curved passage using special machinery. Dunhill had a long relationship with these same makers that began as early as 1915, having bought pre-turned bowls from St. Cloud prior to opening his own factory, and later acquiring French-made frasing machinery, even hired French workers to operate the machines and train his craftsmen. Indeed, it's entirely possible that he first saw this shape at his St. Cloud suppliers. Below is an example of such a pipe, far larger even than the LC, and executed by the old Genod company in about 1920, which I purchased from the grandson of Henri Genod, who had hidden a cache of very old pipes in the basement of the factory to save them from the Nazis. It had a skillfully executed curved air passage, of course.

But there was only one man in St. Cloud who knew how to do this drilling. The French, being quite proud and at that time in an intense competition with the British for prominence in the world of pipes, almost certainly refused to share this technology with Dunhill to preserve what remained of their competitive advantage. This left Dunhill with only one alternative to make a smokable pipe in this shape: cut the shank, drill the two portions at slightly different angles, and then rejoin the cut, thus approximating a curved air passage. Note also that the Genod pipe shown above has the same shape bowl as that of the LC, with the slight bulge at the forward edge of the heel! (This feature was pointed out to me last year by the Luigi Crugnola of Gigi Pipes, a famous Italian pipe maker of some 50 years experience). This lends further weight to the French origins of this shape.

Why would Dunhill lavish such attention and care upon a pipe when he was already extremely successful in the business, having far surpassed in revenues and reputation the older British makers like Barling, BBB and Comoy? Indeed, we know that more than one "spliced shank" LC was made and sold because John Loring, the leading scholar of the Dunhill pipe, has one in his personal collection. So it's fair to say that Dunhill was willing to risk the reputation of his company in order to introduce this shape to the market.

My own belief is that Dunhill became personally fascinated with the shape, and hence was willing to go to any length necessary to produce and sell it. It's not impossible that he himself carved some of the early examples or at the very least personally supervised their production. I share this fascination, and have been experimenting with this shape for over five years, as documented here. I find it one of the most beautiful and archetypal classical pipe shape ever made.

For Dunhill, the gamble paid off: this shape became the foundation of a series of designs which themselves became iconic in the world of pipes, including the shapes 53, 56, 120, and 622.

Although I have seen and marveled over Loring's collection of LC's this is the first I have ever had in my workshop, much less offered for sale. I acquired it from Mike Reschke, long-time collector and past President of the Chicago Pipe Club, the largest such organization in the United States. He in turn had acquired it 20 years ago from an elderly British collector who apparently smoked it rarely if ever.

So in sum, we have here a very important historical piece, one of superb quality. It is as close to an unsmoked example as one is ever likely to find. And lest we forget, it is a wonderful smoking instrument.